Kagwiria Karimaiga Dance Group, Meru’s fight for a greener future.

In Meru County, where climate shocks are increasingly threatening livelihoods, a group of women has turned tradition into activism. The Kagwiria Karimaiga Dance Group, known locally as the “Dancing Queens of Meru”, use rhythm and recycled plastic to rally their community against climate change. Their moves carry more than entertainment but of survival.

On a bright afternoon in Imenti North, the sound of sticks striking hand-held plywood shields fills the air. The women, dressed in yellow bonnets, yellow shirts, sisal skirts layered over green wraps, and strings of recycled plastic bottle tops jingling at their waists and necks, move in rhythm.

Forty women, aged between 20 and 75, have transformed traditional dance into a powerful act of environmental conservation.

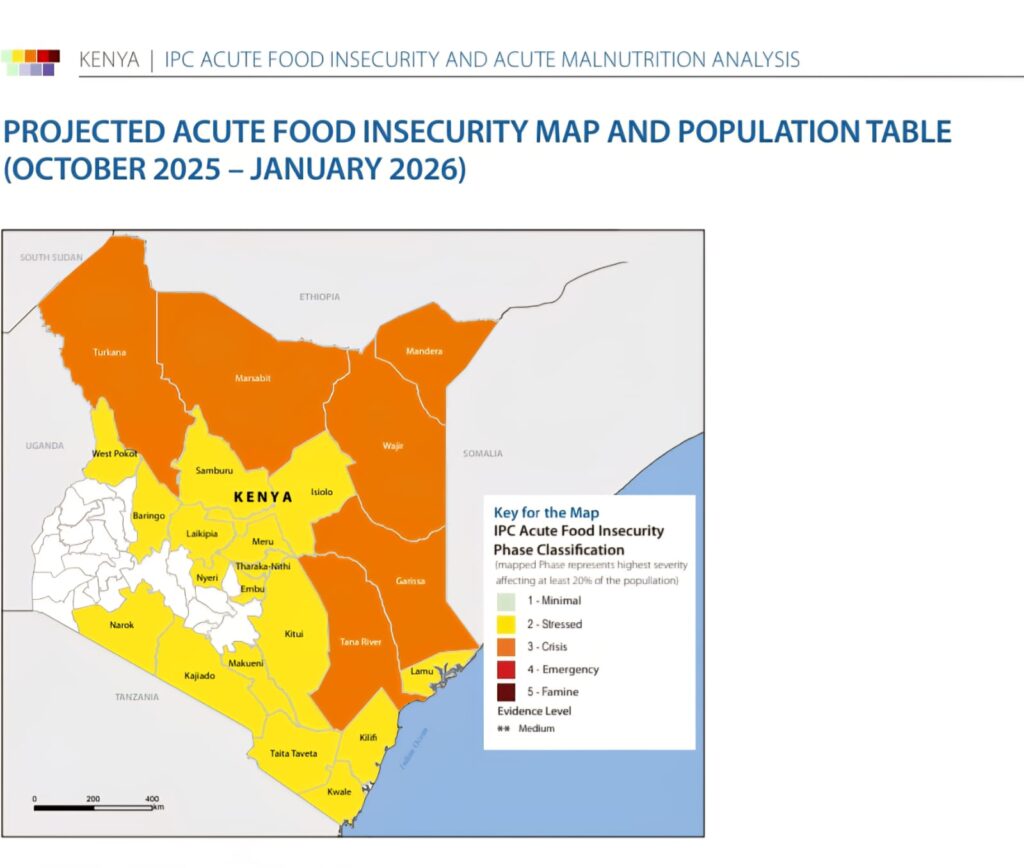

Meru, often celebrated for its fertile highlands and thriving agribusiness, now stands at the frontline of Kenya’s climate crisis. According to the latest IPC (July 2025–Jan 2026) analysis, about 79,500 people 10% of Meru’s population are facing acute food insecurity (IPC Phase 3 or worse).

While not as dire as in Kenya’s arid counties, the trend underscores a growing vulnerability, as prolonged dry spells and erratic rainfall undermine both farming and food security.

“We plant tree nurseries, we supply seedlings to the Kenya Military in their reafforestation programs, and we keep plastics from littering our villages,” says Agnes Makinya, the group’s Secretary General.

“If you visit any member’s home, you will not find a plastic carrier bags we collect plastic bottles and caps, recycle them into ornaments, and dance with them proudly.”

Semi-arid sub-counties including Igembe North, Igembe South, Tigania East, Tigania West, and Buuriare hardest hit. Farmers lament repeated crop failures in maize, beans, and bananas staples once synonymous with Meru’s bounty. Livestock losses are mounting, while rivers and springs dry up earlier each year.

Reduced harvests force families to buy food at inflated prices, deepening their struggles. But where the data highlights crisis, the women’s dancing feet bring hope.

The group traces its roots to 1987, when it was formed to preserve Ameru culture. By 1997, it was officially registered and later embraced a broader mission: protecting the environment. They became protégés of the Green Belt Movement, founded by Nobel laureate Wangari Maathai.

“We are a product of Wangari Maathai,” Agnes recalls with pride. “We were even honored to welcome her at the airport with our dance after she won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2004.”

Their activism goes far beyond performance. Twice a month, the women lead market clean-ups, garbage collection, recycling drives, and tree planting in schools, homesteads, and degraded lands. Their nurseries supply seedlings not just locally but also to Kenya’s Air Force and the 4th and 10th Battalion of the Kenya Army.

For Fridah Kinya, a member of the group, the link between climate and survival is clear.

“When trees are cut it affects the rain pattern. It affects farming and food production for our children. When it floods due to climate change our children will be homeless, our farms are washed away.”

She adds, “When rainfall is not enough we face losses as farmers too, we spend a lot on fertilizer and seeds but end up with little produce compared to the cost of input. So we end up with food insecurity.”

Her words echo the IPC findings: erratic rainfall, crop losses, and food insecurity are no longer distant threats but lived realities in Meru.

Beyond food security, the women see environmental conservation as essential to healthy communities.

“At the end of the day every food production is affected. Environment conservation helps us even in getting clean air for the people. We need to do this for our country and its future. We also plant trees in our villages,” Fridah adds.

Through dance, the Kagwiria Karimaiga women make conservation visible and joyful. They show how culture and climate action intertwine. With each beat of their shields, each shake of their sisal skirts and bottle-cap ornaments, is a reminder that women are on the frontlines of climate change.

And their work carries a social edge. Modest earnings from cultural performances help buy food and support their families. “Volunteering comes from the heart,” Agnes insists. “But women must also survive. Through conservation and culture, we sustain both the environment and our households.”

At the United Nations General Assembly in New York, President William Ruto called on global leaders to treat Africa as a partner in climate justice, not a victim. “Equity is not charity it is justice,” he declared, urging investment in renewable energy and local solutions.

In Meru, the Kagwiria Karimaiga women demonstrate how climate action extends beyond international platforms, taking root in villages, markets, and cultural spaces where tradition intersects with resilience.