When the soft notes of Jamaica Farewell drifted through the speakers at Nyayo National Stadium, the air went wild, Dignitaries, military officers, clergy, and thousands of Kenyans stood shoulder to shoulder, united, former Tanzanian president Jakaya Kikwete was seen unbuttoning his coat ready to jig.

The DJ cued the familiar tune and President William Ruto began the first line:

“But I’m sad to say, I’m on my way, won’t be back for many a day…”

Ruto, standing before a nation draped in mourning, sang with a trembling voice the verse Raila Odinga loved most. It was a moment both surreal and intimate: his broad-based government partner, paying tribute to a fallen giant with the very song that once made him dance.

“That was one of his favorite songs,” Ruto recalled. “A melody of longing and gentle sorrow. He often broke into dance and, with a big smile, sang…”

“Down the way where the nights are gay

And the sun shines daily on the mountain top,

I took a trip on a sailing ship…”

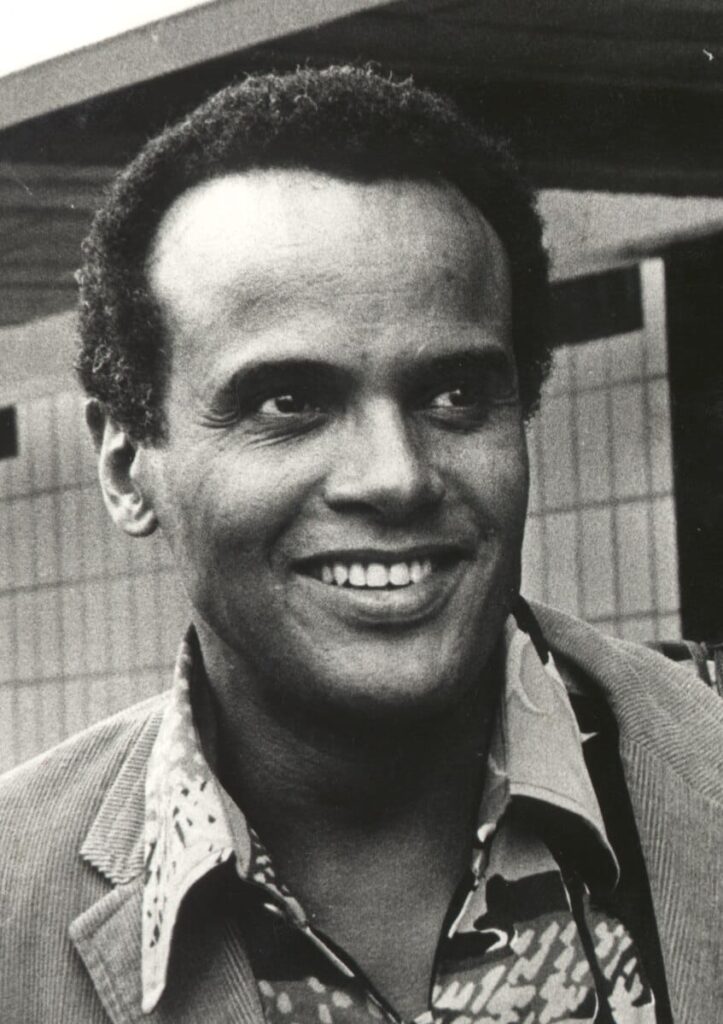

For decades, the Harry Belafonte classic had been Raila’s quiet anthem a melody he turned to in moments of reflection and triumph alike. But on this October afternoon, it became Kenya’s collective goodbye.

Raila Amollo Odinga, Kenya’s long-time opposition leader and one of Africa’s most enduring political figures, was not just a statesman. He was, as those close to him often said, “a man of rhythm.” Music threaded through his life.

During the eulogy, his daughter Winnie Odinga recalled, her voice trembling:

“At home, he was gentle and humorous. He loved storytelling and music, I think you all know his favorite song.”

Then, through held-back tears, she began to sing:

“But I’m sad to say I’m on my way,

Won’t be back for many a day.

My heart is down, my head is spinning around,

I had to leave a little girl in Kingston town.”

The mourners joined her, line by line, word for word. Every lyric, every rhythm Raila’s song blanketed the stadium.

Former President Uhuru Kenyatta was spotted at the service, moving rhythmically to the beat, his face breaking into a nostalgic smile. As the crowd sang “…for many a day, my heart is down…”, Uhuru joined in his hands swaying, shoulders relaxed, mouthing every lyric with the ease of one who had sung it many times before.

Jamaica Farewell, the 1956 ballad made famous by Harry Belafonte, was written in the spirit of Caribbean nostalgia. It speaks of departure and longing of sailors leaving behind lovers and islands. Yet for Raila, it symbolized resilience: the bittersweet pull between home and the long journey toward freedom.

Though oceans and eras separated them, Odinga and Belafonte moved to the same beat a rhythm of defiance, justice, and unrelenting hope.

Belafonte used melody as his weapon; Raila wielded words. Yet both sang the same song the anthem of the oppressed.

In 1950s America, Belafonte became the lyrical face of resistance. His music, rooted in Caribbean soul and African struggle, carried messages beyond dance halls and radio charts. His stage became a protest ground, his fame a megaphone for movements the world preferred to ignore. He fought for inclusivity and end of arpatheid.

Across the Atlantic, in a Kenya still wrestling with the aftermath of colonialism, Raila Odinga was finding his own voice of rebellion. Where Belafonte sang of exile and return, Raila lived it. He endured imprisonment, torture, and political isolation yet every time he emerged, he carried the same unbroken rhythm of resistance.

Both men believed freedom was not a gift from power but a song that must be sung again and again until the world listens. Belafonte sang for civil rights alongside Martin Luther King Jr.; Raila marched for democracy, often at the cost of his own freedom. One fought with melody, the other with movement both refused silence.

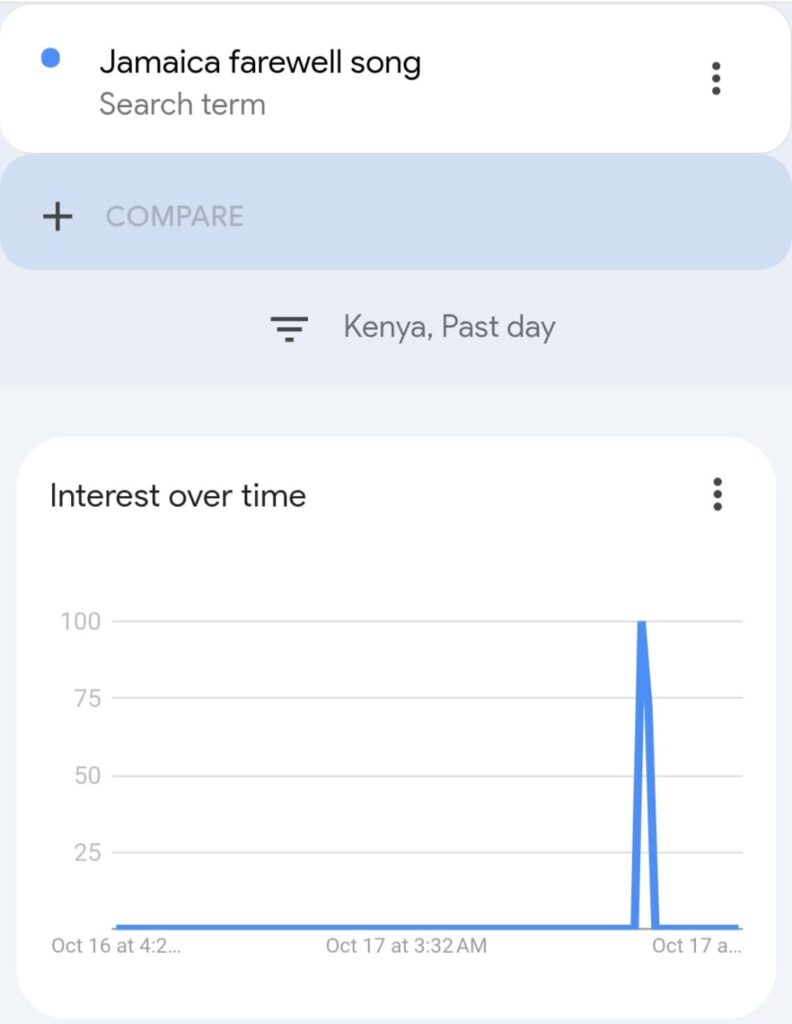

A Spike in Search

Within hours of the news of Raila’s death on October 15, 2025, Kenya rediscovered Jamaica Farewell.

According to Google Trends, searches for the song spiked sharply that night. For months, it had barely registered in local data. By evening, it was among the most searched pieces of music in the country.

On YouTube, Belafonte’s original version surged from a few thousand views to millions. The comment section became an impromptu condolence book:

“Here because Baba loved this song. ❤❤ Like it.” — Kennedy Sewe

“Kenyans, let’s gather here… Shine on your way, Baba 😢😢😢.” — Nesten Stephen-shyn3

“Listening to this after the demise of Raila Odinga 😢 Rest in peace Baba RAO.” — Hazel Niveah

Each line read like a verse of its own a national choir of mourning.

When Winnie sang the song again later that day, she paused, exhaled, and pressed on, finishing the final stanza through tears. Clips of her performance went viral on X, TikTok, and YouTube, drawing millions of views within hours.

“Winnie sang her father home,” one user wrote. “That song will never sound the same again.”

It is curious how a song about a distant island could become a Kenyan requiem. Yet Jamaica Farewell carries universal themes longing, exile, love of home that mirrored Raila’s journey.

He often described his life as one of “constant motion.” He spent nearly a decade in detention, went into exile, and returned to lead movements for democracy. When the song played at his state funeral, mational mass, it transcended geography. What once belonged to the Caribbean now belonged to Africa and to Kenya’s memory of its most resilient son.

TikTok became a mourning wall: thousands posted clips under the hashtag #FarewellBaba, pairing the song with old campaign footage, archival interviews, and videos of Raila dancing.

By midday on October 17, Jamaica Farewell’s comment section had transformed into a digital shrine:

“RIP Raila Amollo Odinga. A soldier has rested. Kenya is mourning 😢😢😢.” — @jaymaimah5834

“I’m here because of our icon Raila Amollo Odinga. Go well, father of democracy.” — @denniskimutai9639

“A great man has died today, and this was one of his favorite songs. Rest in peace, Baba 💔.” — @kabitijr1201

“Baba brought me here… continue resting with the angels.” — @clevies3938

Lines like “My heart is down, my head is turning around” echoed the emotional exhaustion of a man who spent his life fighting for change. The “many days” he sang of now sounded prophetic a metaphor for absence, remembrance, and legacy.

In Kenya’s cultural memory, some songs define eras: Unbwogable marked political awakening, Wimbo wa Historia captured liberation, and now Jamaica Farewell anchors remembrance.

“But my heart is down, my head is turning around,

I had to leave a little girl in Kingston town.”

Perhaps , just maybe, maybe , this was Baba’s final promise that the voyage continues, even as he leaves his beloved Kenya behind.

The Meaning Behind the Melody

At its heart, Jamaica Farewell is a song of parting a tender goodbye wrapped in island rhythm.

It tells of a traveler leaving Jamaica, torn between the joy of the island’s beauty and the sorrow of leaving someone he loves behind. Through its simple verses, one feels the warmth of sunlit shores and the ache of distance the pain of saying farewell to a “little girl in Kingston town,” with no promise of return.

Though its melody flows lightly, the song carries an undercurrent of longing. It celebrates the Caribbean’s laughter, color, and rhythm while mourning the separations life demands.

Harry Belafonte’s rendition transformed it from a local calypso tune into a universal ballad of love, loss, and memory. For millions, it became the sound of nostalgia not just for Jamaica, but for every home, dream, and loved one left behind.

About the Song

Title: Jamaica Farewell

Artist: Harry Belafonte

Writer: Irving Burgie (Lord Burgess)

Year Released: 1956

Genre: Calypso / Folk

Themes: Nostalgia, exile, longing, return

Kenyan Connection: Raila Odinga’s favorite song sung at his funeral service by his daughter Winnie Odinga and President William Ruto.